I hurried to get dressed, trying to remember my "warm formula"…one medium layer of thermals under the jeans, a thick layer of winter thermals over the jeans, an under shirt, two sweaters, a short length down coat, long thick wool scarf around my nose and mouth, a rabbit fur hat that covers my ears, two pairs of gloves, thick wool socks, sheep wool lined Ugg boots fitted with yak traks to keep from slipping on ice… I should hurry. My English class starts in an hour and a half and it's a 45-minute walk to the orphanage. No time for breakfast; I will have to wait until lunch when I eat with the kids. I leave some dried food out for the cats and walk out of my Russian style apartment building passing the trash lady in my cold graffiti ridden stairwell. I weave through New Darkhan through a shortcut of alleyways and narrow cracks between buildings. I ignore the holler of the meeker-seekers' "Yvax uu?" for I rather walk the long distance in -30C than pay 250T for a taxis ride one-way. My PC salary doesn't allow for such luxuries. I reach the long stretch of road that leads directly to the orphanage; I can see it in the distance. The field next to the road is barren so the wind blows extra hard during this stage of the walk. My throat and nose are being to hurt from breathing in the cold air. I pull my scarf tighter around my mouth. I finally reach the orphanage compound and walk through the main building. Khishgee, caretaker of the day, greets me and then asks why I am there. She then proceeds to tell me that all the teachers are on holiday that week, which includes me. Didn't I get the message? I had not though I've gotten used to being told important information at the very last minute. I put back on my scarf and start the cold journey back home.

Burengiin Nuruu Mountain Range

History of the Peace Corps Program in Mongolia

Country Assignment

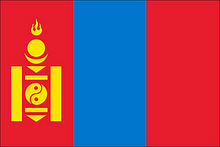

- Country: Mongolia (Outter)

- Program: Youth Development

- Job Title: Life Skills Trainer (also: English teacher, Child Caretaker, Fund Raiser, Events Organizer, and IT Trainer)

- Orientation (Staging in Atlanta, GA): May 31-June 2, 2007

- Pre-Service Training (in Darkhan and Sukhbaatar, Mongolia): June 3-August 18, 2007

- Dates of Service (in Darkhan at Sun Children formerly "Asian Child Foundation" - a non-profit, non-government Japanese funded orphanage of 37 Mongolian children opened since 8/25/2005): August 19, 2007- August 18, 2009

Location and Nature of the Job

CYD Volunteers are placed in provincial centers with population between 15,000 and 70,000. A few CYD Volunteers are placed in Ulaanbaatar, where the population is reaching 1 million. I will work with youth-focused NGOs, children’s centers, schools, and civil society organizations to address major challenges confronting Mongolian youth today, such as education, life skills, employability, and leadership. In addition, the work will involve workshops and presentations at schools and community agencies and will entail traveling to other outlying communities that have less access to information and training. Given the vast distances in Mongolia, these visits will often require overnight stays.

Monday, January 21, 2008

A Typical Monday in January

Wednesday, January 9, 2008

Article: Too Many Innocents Abroad

By Robert L. Strauss; former Peace Corps volunteer, recruiter and Cameroon country director. He now heads a management consulting company.

The Peace Corps recently began a laudable initiative to increase the number of volunteers who are 50 and older. As the Peace Corps' country director in Cameroon from 2002 until last February, I observed how many older volunteers brought something to their service that most young volunteers could not: extensive professional and life experience and the ability to mentor younger volunteers.

However, even if the Peace Corps reaches its goal of having 15% of its volunteers over 50, the overwhelming majority will remain recently minted college graduates. And too often these young volunteers lack the maturity and professional experience to be effective development workers in the 21st century.

This wasn't the case in 1961 when the Peace Corps sent its first volunteers overseas. Back then, enthusiastic young Americans offered something that many newly independent nations counted in double and even single digits: college graduates. But today, those same nations have millions of well-educated citizens of their own desperately in need of work. So it's much less clear what inexperience Americans have to offer.

The Peace Corps has long shipped out well-meaning young people possessing little more than good intentions and a college diploma. What the agency should begin doing is recruiting only the best of recent graduates – as the top professional schools do – and only those older people whose skills and personal characteristics are a solid fit for the needs of the host country.

The Peace Corps has resisted doing this for fear that it would cause the number of volunteers to plummet. The name of the game has been getting volunteers into the field, qualified or not.

In Cameroon, we had many volunteers sent to serve in the agriculture program whose only experience was puttering around in their mom and dad's backyard during high school. I wrote to our headquarters in Washington to ask if anyone had considered how an American farmer would feel if a fresh-out-of-college Cameroonian with a liberal arts degree who has occasionally visited Grandma's cassava plot were sent to Iowa to consult on pig raising techniques learned in a three-month crash course. I'm pretty sure the American farmer would see it as a publicity stunt and a bunch o f hooey, but I never heard back from headquarters.

For the Peace Corps, the number of volunteers has always trumped the quality of their work, perhaps because the agency fears that an objective assessment of its impact would reveal that while volunteers generate good will for the United States, they do little or nothing to actually aid development in poor countries. The agency has no compressive system for self-evaluation, but rather relies heavily on personal anecdote to demonstrate its worth.

Every few years, the agency polls its volunteers, but in my experience it does not systematically ask the people it is supposedly helping what they think the volunteers have achieved. This is a clear indication of how the Peace Corps neglects its customers; as long as the volunteers are enjoying themselves, it doesn't matter whether they improve the quality of life in the host countries. Any well-run organization must know what its customers want and then deliver the goods, but this is something the Peace Corps has never learned.

This lack o organizational introspection allows the agency to continue sending, for example, unqualified volunteers to teach English when nearly every developing country could easily find high-caliber English teachers among its own population. Even after Cameroonian teachers and education officials ranked English instruction as their lowest priority (after help with computer literacy, math and science, for example), headquarters in Washington continued to send trainees with little or no classroom experience to teach English in Cameroonian schools. One volunteer told me that the only possible reason he cold think of for having been selected was that he was a native English speaker.

The Peace Corps was born during the glory days of the early Kennedy administration. Since then, its leaders and many of the more than 190,000 volunteers who have served have mythologized the agency into something that can never be questioned or improved. The result is an organization that finds itself less and less able to provide what the people of developing countries need – at a time when the United States has never had a greater need for their good will.

Recommended Books on Mongolia

- “Dateline: An American Journalist in Nomad’s Land” by Michael Kohn, 2006.

- "Ghengis Khan and the Making of the Modern World” by Jack Weatherford, 2004.

- “Riding Windhorses” by Sarangerel, 2000.

- “Twentieth Century Mongolia” by Baabar, 1999.

Recommended Mongolian Movies

- The Story of the Weeping Camel (2004), Die Geschichte vom Weinenden Kamel

- Mongolian Ping Pong (2005), Lü cao di

Notable Articles on Mongolia

Informational Links

- Peace Corps - Mongolia

- International Calling Card (Cheap!)

- Current Mongolian News

- Current Weather Conditions in Ulannbaatar, Mongolia

- A Tour of Mongolia Through Photography

- History of Mongolia

- Mongolian Culture

- Mongolian Lanuage

- Weather and Climate In Mongolia

- Travel Guide to Mongolia

- Official Tourism Website of Mongolia

- Asia.com - Cheapest Airfare to Asia

- MIAT - Mongolian Airlines

- Currency Converter

- Entry and Visa Requirements